ok, now for the actual seminars

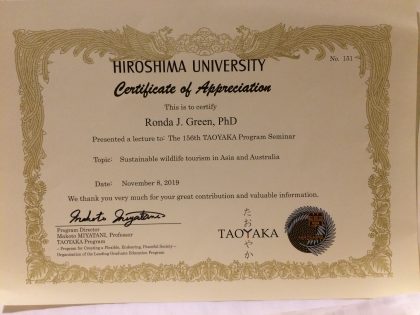

I presented essentially the same talk at Hiroshima University (a beautiful, spacious campus I somehow didn’t photograph – second largest university in Japan) and the Asia-Pacific University in Beppu (adjacent to Oita). The Q and A time at the end of course was more varied.

I am grateful to Rie Usui and Thomas Jones for inviting me to present to these seminars and giving me the opportunity to see small part of Japan’s wildlife tourism (I know there is much more to see!). It was also good to meet Carolin Funck, whose co-authored papers with Rie I had read, Malcom Cooper who kindly gave me a copy of his co-edited book on the Natural Heritage of Japan, and other staff and students.

Read about some of Thomas Jones’s research here and research by Rie Usui here

The powerpoint was a little hungry on memory, so I’ve replicated it here as a 5-part pdf. I’ve mostly uploaded it here for students who ha to miss the seminar because of schedule clashes, but others are also welcome to download them, and ask questions in the comments section below

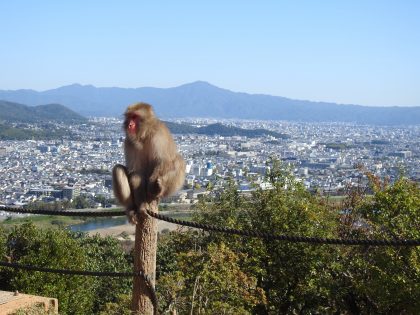

One of the questions after the first seminar (at Hiroshima University) was what I though of the dilemma of feeding monkeys at the monkey forest near Beppu. They have tried feeding them less to encourage more natural behaviour but then less monkeys – sometimes no monkeys at all – turn up and visitors are very disappointed. I later saw this for myself, visiting that forest one day and seeing something like 2300 monkeys, and noticing as we drove past the following day ghat no monkeys had arrived. I suggested some kind of guarantee that if a visitor finds no monkeys present they get a free voucher for another day or perhaps a nice souvenir with a monkey motif. I was asked at the Beppu seminar what I thought of a tourist activity in one part of Japan involving shark-finning. Questioning the questioner I learned that it wasn’t the very cruel practice of slicing the fin from a living shark and leaving it to slowly die (I walk out of any restaurant serving shark fin because of this common practice), but capturing the shark and processing the whole animal, including the fin. I said I still don’t like this being a tourism activity (it’s not much fun for the shark, and I have a distaste for killing being fun for the human participants) but if any kind of fishing or hunting is to be included as tourism (or for food production) it should at least ensure a sustainable harvest that doesn’t threaten the species, and should also kill the animal as quickly and humanely as possible.

Another monkey forest

Two days before the seminar at the Asia-Pacific University in Beppu, I went with Tom and his two eldest children to the monkey forest at Takasakiyama National Park. About 200 monkeys had gathered for feeding by staff (visitors do not feed them at this park). Most visitors appeared to be Japanese, or at least Asian: there were nowhere near so many westerners at at Arishiyama Monkey Forest.

Another difference was that many young monkeys were playing, either climbing the monkey playground equipment, chasing each other, or engaged in playfights. I have only seen a few examples of play at Arishiyama. One reason may have been the monkey playground, but many youngsters were playing elsewhere. Probably it was due to a difference in temperature rather than the place itself: I was at Arishiyama in the heat of mid-day and at Takasakiyama much later in the day. One staff member told us (in Japanese, through Tom: as at Arishiyama there didn’t seem to be any English-speaking staff) they didn’t feed sweet potatoes (the monkeys’ favourite) util the end of the day, t encourage the monkeys to stay as long as possible.

Similar to Arishiyama, monkeys seldom made eye contact with humans, just casually strolling by without acknowledging their presence in any obvious way. Just one young monkey doing acrobatics on some metal railing looked up at Tom and myself in brief communication before resuming his activities. Prolonged staring is a sign of aggression amongst these monkeys, but I was surprised in both localities there was so little by way of even fleeting eye contact.

One other difference was a monkey museum with lots of information for visitors

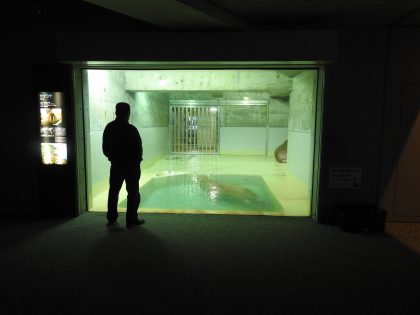

Aquarium

Next door was the Umitamago aquarium, which w visited next day (and were surprised to find that despite the abundance monkeys the day before, none had shown up that day to the feeding area, although we arrived at a similar time of day). There was a good collection of species, including a number that were endemic to Japan, and found in the Oita/Beppu area, and a number of awards for success in breeding

I liked the emphasis on making friends with the animals, seeing them as living beings to appreciate and communicate with. I’m well aware of the controversy surrounding animal performances but it did enthral the crowd, who may thus develop a softer spot for the animals. I had the impression that the walruses and seals had a good relationship with their trainers (I’ve trained a number of horses and dogs, and seen the behaviour of those trained by others in both gentle and rough ways), and it probably at least gave the animals something to do to break the boredom: most returned to very dull cement cages with no enrichment objects in sight. Japan has had a reputation as a very innovative country for decades: I would love to see some innovation here to make daily life more interesting for these intelligent creatures. The dolphin enclosure also needed to be much bigger and more complex to keep these animals entertained, and I brought up the topic during my talks as to whether dolphins should in fact be kept in captivity at all (there seemed to be unanimous agreement that whales shouldn’t).

The main aquarium had more space and more complicate topography for the animals. The fish, including the big manta rays, knew exactly why the diver appeared with a bucket of food.

All in all a very nice aquarium conducting some successful breeding of rare species and presenting some good displays with information on the species and their ecology, although I would have liked to have seen a bit more visitor education (and of course a bit more in English: Chinese and other languages would also be helpful for visitors), and, as above, some larger and more stimulating enclosures.

—————————————-

Once more, many thanks to Rie and Thomas for inviting me, and to both the universities and Wildlife Tourism Australia for financial support for my airfares and some of my accommodation. I was also treated to some lovely meals in Hiroshima and Beppu.

Japan has a lot more wildlife and both terrestrial and marine wild places than most tourists realise (stretching from subtropical to subArctic, and over 6000 islands), and much potential for quality wildlife tourism. I wish I could have explored some of the wilder areas – maybe next time! It is good to see the interest now being shown in the topic, and I’ll be watching with interest what happens there over the next few years.